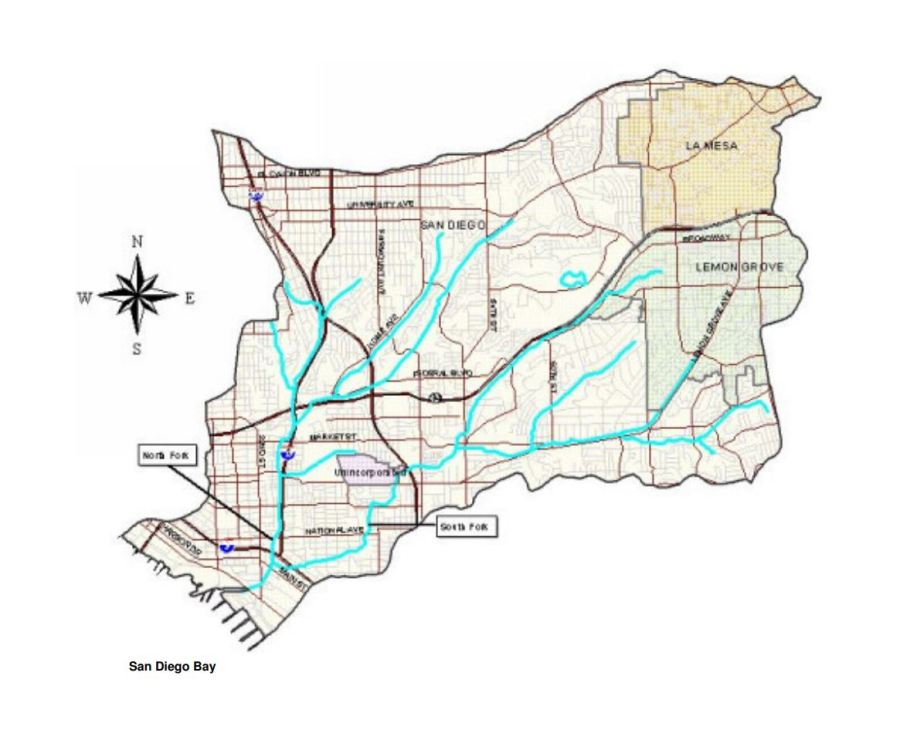

Imagine a map of San Diego County riven through with a series of crooked, twisting capillaries, all headed toward 7 o’clock, combining into bigger and bigger veins, until, nearly to the coast, they gather into two thick arteries that, after passing under Interstate 5, merge into a single waterway north of Naval Base San Diego.

Just before that southern digit dives under the Five to carry away all of the water in the 16,000-acre Chollas Creek Watershed, though, is Chollas Creek itself, an approximately 30- to 40-foot wide concrete-sided trough that, on Jan. 22, pulsed with millions and millions of gallons of water, rain that fell on Spring Valley and Lemon Grove, both of which experienced torrential flooding; that fell on sections of I-15 and I-805; that fell on National City, where scores of people were displaced by flooding; and that fell on the San Diego neighborhoods of Encanto and Mountain View. All that water finally collected and pooled in, under and around the communities of Southcrest and Shelltown, where it sought any egress it could, whether that was the creek itself or an alley running behind Beta Street, or into and through 400-500 homes, many occupied by immigrants or families from underserved populations, many of them, if not most, among the poorest people living in San Diego,

Now, weeks after the flooding that submerged those communities before the stormwater finally ran out to the sea, bulldozers and bobcats have, under the umbrella of an emergency declaration, finally scraped the creek — “dredged” it, in bureaucrat parlance — and so, during last week’s pineapple express, it was finally up to the job, taming a raging river but this time mastered by the hands of engineers.

As bad as things were on Jan. 22, they would have been even worse if not for Hurricane Kay. You may remember the “hurricane” that arrived in San Diego in September 2022 as Tropical Storm Kay. On Sept. 9 of that year, San Diego set a new daily precipitation record for that day of 0.59 inches of rain, beating the old high of 0.09 inches set in 1976, according to the National Weather Service of San Diego.

The week before the 9th of September, the staff at the city’s stormwater department also obtained an emergency declaration, based on a weather forecast of 0.7 inches, prompting city crews to spring into action in what is known as Alpha Channel, the one down by Southcrest and Shelltown.

Flooding in San Diego

Workers scrambling over the course of two days managed to clear 2,178 tons of “accumulated sediment, vegetation and debris” from a 442-linear-foot section of the waterway and from Ocean View Channel in the Mountain View neighborhood, about a mile to the north, where flooding also occurred on Jan. 22. The problem was, in the words of a nameless city worker, “accumulated material had constricted hydraulic capacity” in the channel, prompting the work on both sides of the 40th Street Bridge.

San Diego's flood-channel maintenance program

The city of San Diego has hundreds of flood channels, each approximately 1,000 feet or so. They don't all need dredging, but there are plenty that do.

“Currently, we’re budgeted to do about four channel cleanings every year,” said Kris McFadden, a deputy chief operating officer for the city who oversees stormwater, transportation and public utilities.

A bullet-headed, bespectacled man clad in a sensible blue suit, white button-down and red-and-blue striped tie, McFadden, who came up out of the stormwater department and has worked for the city for nearly 16 years, according to his LinkedIn, braved a half-dozen or so reporters at a hastily arranged news conference three days after the storm, sitting at the far end of a very long conference table and armed only with some notes and a large water bottle.

Each year, McFadden and his staff select that handful of channels to clear.

“This is a creek that’s been around for millennia,” McFadden said. “It’s a creek. It’s not when you look at Los Angeles and they have the big wide concrete corridors and aqueducts that convey water. This is a creek.”

To some degree, the stormwater department decides which channels to clear based (pending city approval) on input from the community, but it also undertakes an annual survey to make its final selections.

“We look at risk management: ‘So, what is the likelihood of something failing, and the probability and consequence of that failing?’ ” McFadden told the media. ”We have over 200 channel segments throughout the city and we cannot do all of them, unfortunately, at once.”

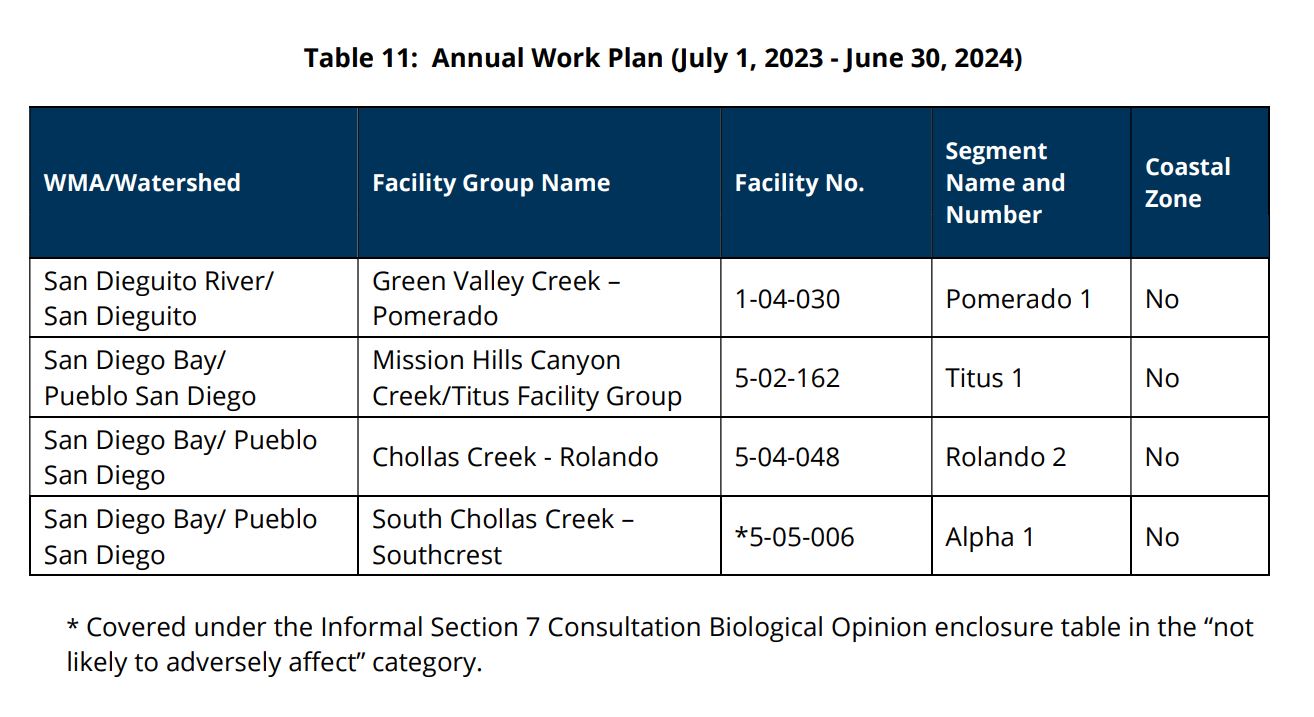

Sadly for the residents of Shelltown and Southcrest, Alpha WAS on the list of four channels to be cleared in 2023-24, as was the Pomerado Channel up in Rancho Bernardo, the Rolando Channel in the Chollas Creek Watershed, and the Titus Facility Group near Mission Hills Canyon Creek.

Last week, a colleague of McFadden’s, Todd Snyder, who is the city's stormwater department director, took part in a news conference as well, this one with a small group of other city officials at which they were discussing the response to the atmospheric rivers that drenched Northern California and LA but spared San Diego from the worst.

According to Snyder, the city has a crew of 15 people for channel clearing and dredging. San Diego currently has “over 12,000 skilled and dedicated city of San Diego employees," according to the city's employment page.

“Now, because of environmental regulations, typically what we can do to maintain channels has to take place between the middle of September and the middle of March,” Snyder said.

Those regulations are in effect then because bird-breeding season takes place during the balance of the year. Remember: It’s the Chollas Creek Watershed, and, as such, is home, at least during the dry portion of the year, to thousands of migratory birds.

Flooding in San Diego

This latest wet season, those 15 workers were first deployed up in Rancho Bernardo, where their tasks were completed, then the crew moved on to Rolando, where the job was halted Jan. 22, when the skies opened up; workers had, at that point, removed 270 tons of sediment and debris, according to Ramon Galindo, a spokesman for the stormwater department. The work they did accomplish, though, was unable to prevent flooding in Rolando on Jan. 22.

No work had been done on Alpha Channel, other than those emergency repairs in 2022.

Snyder said work had been expected to begin on Alpha Channel in February or March. Sadly, that work did take place, but not until the historic storm passed, under a directive from Mayor Todd Gloria. For the now-flooded-out residents living near the southern end of Chollas Creek, it was too late but it still could help residents moving forward since the scope of the project was expanded.

"That work on the Alpha Channel has now been completed through the emergency declaration, which allowed city crews to cover a larger scope than what was originally permitted by regulatory agencies for this project," Galindo said. "We’re still compiling data on the tonnage removed ..."

It’s not yet clear why Pomerado Channel was prioritized over the other dredging projects. NBC 7 has asked the city for an explanation how that decision was arrived at but has yet to hear back.

After the Great Flood of 2024, McFadden called Jan. 22 a “thousand-year storm,” stressing that meant residents in any given year would only experience a 0.01% chance of such an incident. Snyder, for his part, said Alpha Channel, which is about 50 years old, was constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers to handle a 10-year storm, greatly increasing the likelihood of flooding. The "hydraulic capacity," as city engineers put it, of Alpha Channel had to, of course, been "constricted," to again use the official term, due to the presence of large amounts of vegetation, trash and sediment that had built up in the creek since it was last cleaned.

It does not appear that the Alpha Channel was dredged completely during the recent past, according to Galindo.

"In recent years, the [stormwater department] has performed minor maintenance on portions of the Alpha Channel in 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018 and 2020," Galindo said. "Trash and debris removal occurred as well as the removal of invasive plants."

For his part, McFadden said that even if the channel had been freshly dredged, it still would not have had the ability to handle the volume of water that the storm, which parked over the area for hours, dumped on Southeast San Diego in a relatively short time.

“A lot of people say, ‘Well that drain was clogged,’ ” McFadden said the week of the storm. “Well, it could have been from the storm, it could have been, but it’s important to note that, regardless, this system overwhelmed any engineered system that would be designed today.”

In hindsight, it’s unclear whether the storm overwhelmed the channel or clogged the drains, but it seems possible that if Chollas Creek had been dredged before Jan. 22, it might have done a better job mitigating the effects of the storm. What is known is that, while city workers were on what’s called Storm Patrol the day before and the day of Jan. 22, no emergency work had been authorized, despite a forecast of 1-1.5 inches of rain at the coast for Jan. 22, almost double what had been predicted back when Kay swooped in for her wet-weather dance over San Diego.

Also known is the fact that, when an atmospheric river arrived the week after the Great Flood, dropping a little over an inch of rain in a single day, the channel, now cleared under emergency edict, did its job.

NBC 7 has asked the city for an estimate of how much hydraulic capacity the Alpha Channel now has with the emergency dredging completed — how much rainfall it could handle in, say, 24 hours — and is waiting to hear back.

Warnings from the city about the neglected stormwater system

City officials have been crying out, Cassandra-like, for years about San Diego's badly neglected stormwater system, but the issue was highlighted in January, of course, in a way it never had prior.

So far, the response from city leaders is that they were prepared for the storm but could not have possibly predicted an unprecedented act of nature, NBC 7 reported in the days after the great flood.

“None of us alive have seen anything quite like this,” Mayor Todd Gloria said in a news conference outside Lincoln High School the day after the great flood.

NBC 7 Chief Meteorologist Sheena Parveen said that week the hardest hit areas in the county saw, at most, 2 inches of rain per hour over three hours.

“It wasn’t feet of rain,” Parveen said. “We didn’t see feet of rain.”

Parveen said the areas that with the greatest accumulations would have only seen 6 inches of rain total.

“Something else is going on,” Parveen said, “because that’s not coming from just 4 inches to 6 inches of rain.”

Flooding in San Diego

The city said a lot of factors played a role in the flooding in addition to the intense rainfall. A spokesperson said the flooding around Chollas Creek occurred downstream from most of the county, so that area received all the floodwater from La Mesa and Lemon Grove as well. They also pointed out that many of the neighborhoods were built in flood plains and were close to flood channels, saying developers would never be allowed to develop those areas these days.

City officials don’t deny the stormwater infrastructure is aging, but leaders have been adamant there wasn't much any city could have done to prevent the outcome.

“The amount of water that we saw yesterday would have overwhelmed any city’s drainage system,” Gloria said multiple times during that Tuesday news conference.

However, four months ago, city leaders predicted this level of devastation in on-camera interviews with NBC 7 Investigates. At the time, city engineers took NBC 7 inside San Diego’s deteriorating stormwater system.

No single mayor or city administration is responsible for the current state of the city’s stormwater system, of course. The neglect took decades. A fix is projected to be a costly one, with money the city says it doesn’t have.

How can we stop the next great flood?

The term “thousand-year storm,” while impressive, doesn’t carry the gravitas it did even just a few years ago, not since the advent of climate change.

Snyder, the San Diego stormwater director, told NBC 7 that, in the past, the stormwater department has fallen short about $300 million each year. The total deficit for the overall system stands at well above $1 billion. San Diego got a multimillion-dollar grant for some design plans for a few new pump stations, but it’s nowhere close to catching up to that deficit. Snyder said that even these days, though, nobody engineers a storm channel that could manage a thousand-year storm.

“So the gold standard generally, if you're going to be building a channel today, is a 100-year flood,” Snyder said. “That's generally what's seen as the appropriate level of channel design.”

So, even if the Alpha Channel had been scraped and cleared, it could not have eliminated the threat on Jan. 22, Snyder said, even if the vegetation had been removed.

“What we saw with those intense rain events on Jan. 22 were well beyond a 10-year storm,” Snyder said. "Over an hour- to two-hour duration was 1,000-year storm intensities.”

Any prophylactic response to the flooding will be hamstrung by the encroachment, up and down Chollas Creek, of housing. To truly solve the problem would require engineering a bigger channel, which would require property acquisition because people have built up against the channel since it was constructed decades ago.

Flooding in San Diego

The flood channel is lined on one or both sides with concrete, but its bottom is soil and silt. While digging deeper seems like an obvious solution, it’s ill-advised from an engineering standpoint because doing so would compromise the integrity of the channel itself, threatening the soil beneath nearby structures.

And to get that approved would be a minefield inside a morass. Just to do the dredging requires a labyrinthine regulatory process, officials said. The Cholla Creek Watershed is a jurisdictional wetland regulated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, Cal Fish and Game, the regional water-quality control board and, if it’s in the coastal zone, the California Coastal Commission, McFadden said, and approval is required from all of them.

Then, even if the approval is granted, wetlands mitigation credits would need to be purchased from the federal government.

The end-around emergency declarations only forestall the inevitable red tape: Even if the exception is obtained, officials have to file all the paperwork so it can be applied retroactively.

Officials have identified one option that can help Southeast and Shelltown, and it illuminates the daunting financial task ahead: There is an alley that runs behind Beta Street in Southcrest, one that flooded badly during the storm, carrying away vehicles and other debris. The alley is essentially a dirt road at this point and has never been worked on before regarding flooding, but there is now a design worked up for it to upgrade and upsize drainage. The work to widen it would require considerable expansion in some spots, because the alley narrows in some locations, which would require buying homes or property, at a minimum.

Any of this work is prohibitively expensive, even with the $733 million the federal government has recently provided to San Diego for stormwater-infrastructure updating. For example: The work on that alley behind Beta Street, a relatively benign-looking three blocks, carries with it a $50 million price tag.

Looming legal action

A series of legal claims has been filed against the city of San Diego on behalf of residents who were recently displaced by storm-related flooding, it was announced on Monday.

The claims allege the city failed to properly manage its stormwater infrastructure, leading to last month's rain-induced flooding that ravaged homes and left many residents without shelter.

Attorneys representing the residents said they are seeking class-action status for those impacted by flooding and also want the city to establish a stormwater utility in order to fund projects to address stormwater infrastructure needs.

Similar claims — which are the required precursors to lawsuits— have been announced since the January floods on behalf of other residents throughout the city.

Nearly 600 homes in the city of San Diego were damaged by the flooding, according to the Salvation Army.

Meanwhile, the city of San Diego, at the direction of Gloria, is waiving fees for waste disposal, building and demolition and building permits and the reimbursement of any recycling costs associated with rebuilding. But is rebuilding in the Chollas Creek Watershed an option, given what’s just happened?

“You could maintain this system all day,” McFadden said. “If we get another storm system like that, it’ll happen again.”

And that thousand-year estimate?

“That’s what the city has really looked at: At re-engineering, knowing that with climate change, all bets are off,” McFadden said, “and we have to expect this type of storm intensity on a regular basis, and we have to prepare for it, and we have to prepare our residents for that. We owe that to them.”

The City News Service contributed to this report — Ed.

This article originally stated that there was light rain on the day of Sept. 9, 2022, when Hurricane Kay hit San Diego as Tropical Storm Kay. In fact, 0.59 inches of rain fell on that day — Ed.