What do you want to be when you grow up?

As a kid, that was my least favorite question. I dreaded conversations with parents and other adults because they always asked it — and no matter how I replied, they never liked my answer.

When I said I wanted to be a superhero, they laughed. My next goal was to make it to the NBA, but despite countless hours of shooting hoops, I was cut from basketball tryouts three years in a row. In my first semester of college, I decided to major in psychology, but that didn't open any doors — it just gave me a few to close.

I was still aimless, and I envied people who had a clear career plan, like my cousin Ryan.

Checking all the 'right' boxes

From the time Ryan was in kindergarten, he knew exactly what he wanted to be when he grew up: a neurosurgeon. Becoming a doctor wasn't just the American dream — it was the family dream.

When Ryan was looking at colleges, he came to visit me. As we started talking about majors, he expressed a flicker of doubt and asked if he should study economics instead. But he abandoned the idea. Gotta stay on track.

In his last year of med school, Ryan applied to neurosurgery residencies. But he wasn't sure if he was cut out for it — or if the career would leave any space for him to have a life. He wondered if he should start a health care company instead. But when he was admitted to Yale, he opted for the residency. Gotta stay on track.

Today, Ryan is a neurosurgeon at a major medical center. Even though he enjoys caring for patients, the long hours and red tape undercut his enthusiasm. He tells me that if he could do it over, he would have gone a different route.

Money Report

The right directions can give us the wrong destination

We all have notions of who we want to be. They're not limited to careers; from an early age, we develop ideas about where we'll live, which school we'll want to attend, what kind of person we'll marry and how many kids we'll have.

These images can inspire us to set bolder goals and guide us toward a career path to achieve them.

But the danger of these plans is that they can give us tunnel vision, blinding us to alternative possibilities. We don't know how time and circumstances will change what we want or even who we want to be — and locking our life GPS onto a single target can give us the right directions to the wrong destination.

Going into foreclosure

When we dedicate ourselves to a plan and it isn't going as we'd hoped, our first instinct isn't usually to rethink it. Instead, we tend to double down and sink more resources into the plan. This pattern is called "escalation of commitment."

Ryan escalated his commitment to medical training for 16 years. Had be been less tenacious, he might have changed tracks sooner. Early on, he had fallen victim to what psychologists call "identity foreclosure" — when we settle prematurely on a sense of self without enough due diligence and close our minds to alternative selves.

Another example: Evidence shows that entrepreneurs persist with failing strategies when they should pivot. Sunk costs are a factor, but the most important causes appear to be psychological rather than economic.

Escalation of commitment happens because we're rationalizing creatures, constantly searching for self-justifications for our prior beliefs as a way to soothe our egos, shield our images and validate past decisions. And it is a major factor in preventable failures.

'One of the most useless questions'

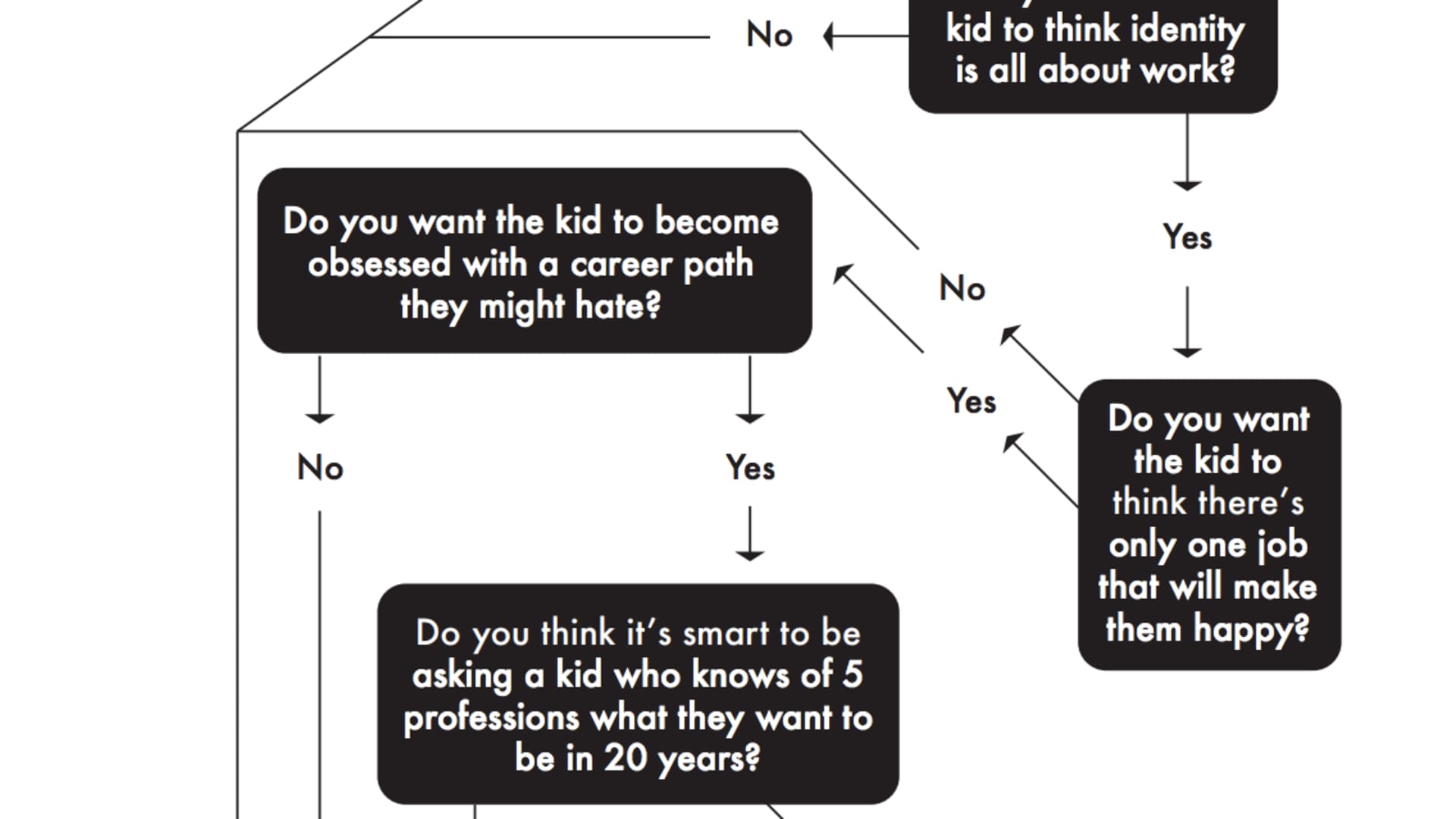

In career choices, identity foreclosure often begins when adults ask kids "What do you want to be when you grow up?" Pondering that question can foster a mixed mindset about work and self.

"I think it's one of the most useless questions an adult can ask a child," Michelle Obama writes. "What do you want to be when you grow up? As if growing up is finite. As if, at some point, you become something and that's the end."

Some kids dream too small. They foreclose on following in family footsteps and never really consider alternatives. Some face the opposite problem: They dreamed too big, becoming attached to a lofty vision that wasn't realistic.

Even if kids get excited about a career path that does prove realistic, what they thought was their dream job can turn out to be a nightmare. Kids might be better off learning about careers as actions to take, rather than their identities. When they see work as what they do, rather than who they are, they become more open to exploring different possibilities.

If your kids do decide to initiate a conversation about what they want to be when they grow up, let them know they don't need to choose one career; they could do many things. Have them brainstorm all the things they love to do — perhaps designing LEGO sets, studying space, creative writing, coaching soccer or being a fitness YouTuber.

Choosing a career isn't like finding a soul mate. It's possible that your ideal job hasn't even been invented yet. Old industries are changing, and new ones are emerging faster than ever before. It wasn't that long ago that Google, Uber and Instagram didn't exist. Your future self might not exist right now, either, and your interests might change over time.

Adam Grant is an organizational psychologist and professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He is the bestselling author of "Give and Take," "Originals," "Option B" and "Power Moves." His latest book is "Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know." Adam received his B.A. from Harvard University and his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrant.

Don't miss:

- I raised 2 successful CEOs and a doctor—here's one of the biggest mistakes I see parents making

- A therapist shares the 7 biggest parenting mistakes that destroy kids' mental strength

- Elon Musk's mom: 'People often ask me how I raised such successful kids'—here's what I tell them

This is an adapted excerpt from "Think Again" by Adam Grant, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2021 by Adam Grant.

Check Out: The best credit cards for building credit of 2021