California lawmakers hope the second time's the charm.

Last year, an effort to limit the use of police dogs never saw the light of day after blowback from police chiefs across California. Now, a new effort to create a statewide policy for all police dogs has support from police groups but rebuke from human rights experts.

“I think anytime you can get standardization of a use-of-force tool for law enforcement, I think that makes sense,” said San Diego Police Chief David Nisleit.

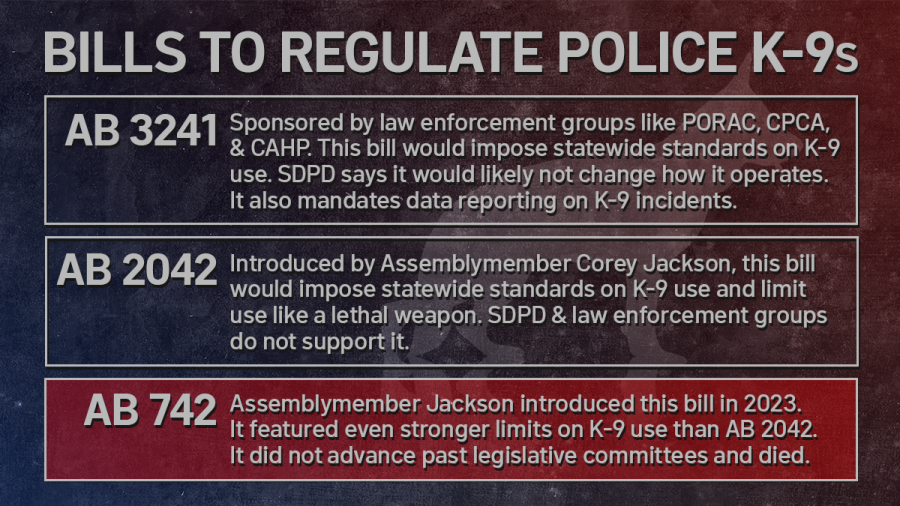

Two state bills, AB 2042 and AB 3241, call for the creation of a single statewide policy for all law enforcement K-9 units. AB 3241 was sponsored by police groups.

“I think this will have a great impact across the state,” said Brian Marvel, president of the Peace Officers Research Association of California (PORAC). PORAC sponsored AB 3241 alongside the California Police Chiefs Association and the California Association of Highway Patrolmen.

Officials with the ACLU of Southern California told NBC 7 that both bills hand over too much power to police, and are too vague to effect substantial change.

“We just need our legislators to stand up for real reform and end police attack dog violence,” said Branden Sigua, senior policy advocate for the ACLU of San Diego and Imperial Counties. “Clear restrictions written into state law make the most significant impact on police practices. Unfortunately, these bills don’t accomplish that.”

There is no statewide standard for how or when police agencies can deploy K-9 units. As a result, each department uses dogs differently, from search and rescue, to bomb detection, to arrests.

Last year, state bill AB 742 tried to limit the use of K-9s to make an arrest. But that bill died after several police chiefs across the state, including San Diego Police Chief David Nisleit, campaigned heavily against the bill. At the time, Nisleit claimed AB 742 would eradicate San Diego’s K-9 unit - a move that he says would have resulted in more violence for both officers and suspects.

“You take that away from my officers, we are going to shoot more people. More officers are going to get hurt,” said SDPD K-9 Lt. Chris Tivanian last year, when asked what would happen if police could no longer use dogs to apprehend suspects.

Police say K-9s are a de-escalation tool

Nearly three dozen (34) dogs and as many handlers comprise SDPD’s K-9 unit. They keep busy. Tivanian said they respond to 2 or 3 radio calls every hour.

SDPD deployed police dogs 10,815 times over a 5-year period from 2018 to 2022, according to records from the city. Of those, 1%, or 161, resulted in a dog bite, SDPD reported. The law enforcement agency counts every time a K-9 exits a police car as a deployment.

“The vast majority of what they're doing is de-escalating situations where we’re taking suspects that are violent, suicidal, into custody with no force. Zero force. They see the dog, they give up,” Tivanian said.

Tivanian says the most valuable thing police dogs bring to an arrest or chase has little to do with any physical traits or abilities of the dogs themselves. It’s their presence alone. Suspects who would otherwise hide or fight back, are often quick to surrender when they learn officers brought a weapon on four legs.

“The psychological effect of that dog gets people to give up when other force options and the police uniform simply don’t have that same impact,” Tivanian said. “The dog does.”

Tivanian considers K-9s the best de-escalation tool on the city’s police force.

“They create time,” Tivanian said. “They create distance. They slow down the situation and make that suspect think twice about what they are doing.”

Both Lt. Tivanian and Chief Nisleit insist their officers do not deploy police dogs on people suspected of nonviolent crimes. However, NBC 7 Investigates repeatedly asked for the specific criminal charges pressed against people bitten by an SDPD K-9. SDPD would not provide that information, saying they don't track that data.

“Why would a public agency fight to not be transparent? That is a red flag,” said Assemblymember Corey Jackson, who also holds a Ph.D. in social work and represents the 60th District within Riverside County.

Previous bill to restrict K-9s failed

Jackson was the author of last year’s AB 742 which tried and failed to restrict K-9 use. This year, Jackson introduced a second attempt, AB 2042, which is still awaiting a hearing.

“I’m hopeful now that they’ve acknowledged that there’s a problem,” said Jackson.

Under Jackson’s new bill, Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST), the state commission that sets standards for law enforcement officer training courses, would be required to create new guidelines outlining when and how law enforcement can use a police dog.

“There are some things only a police K-9 can do,” said Jackson, who supports the use of police dogs in bomb and drug detection, as well as search and rescue.

However, Jackson’s new bill would prohibit K-9s from aiding officers in making arrests unless there is an “immediate threat of death or serious injury.” It’s the same threshold police need to use a lethal weapon.

“You could only use a K-9 if you were authorized to use your firearm. At that point it’s too late,” said Chief Nisleit, who does not support Jackson’s second or first bill.

However, PORAC’s president says it was Jackson who inspired them to sponsor AB 3241.

“We felt that Assemblymember Jackson brought up an issue that hadn’t been addressed. We took what he was trying to do and we improved on it,” said Marvel.

Like Jackson’s bill, the PORAC-sponsored bill requires POST to create standards for police dogs. But it has a lower threshold for K-9 use. Dogs could still help arrest anyone suspected of a “serious offense” that poses a threat of violence to the public or officers, is hiding, or simply, resisting arrest. The bill also requires every police agency to annually post K-9 data, including the total number of K-9 deployments, the number of times suspects surrendered peacefully without releasing the dog, and the total number of dog bites.

“The statistics clearly show that the use of the K-9 de-escalates the vast majority of conflicts that peace officers come into,” said Marvel.

ACLU report highlights disparities and problems with K-9 use

However, an ACLU staff member and policy advocate rejects the notion that a state police commission can effectively regulate its own.

“Police have never policed themselves,” said ACLU regional senior policy advocate Branden Sigua.

In January, ACLU California Action published a blistering report examining the police practice of using K-9s. They determined police dogs were overwhelmingly used on people who did not pose a danger to officers or the public, according to their analysis of public records from 37 police agencies across California.

“They often use K-9s against people who are unarmed, have not been accused of a violent crime, [and] people who are experiencing a mental health crisis,” said Sigua.

That includes an incident in 2015 when an SDPD K-9 bit a naked man, who was high on drugs and not obeying commands. Police body camera video shows the dog kept biting the man for more than 44 seconds after he was on the ground with his hand behind his back.

“The numbers don’t lie,” said Stephanie Padilla, staff attorney for the ACLU of Southern California.

Their review of records from the Bakersfield Police Department revealed that 97% of the agency’s police dog deployments reported by the handler were not used to “defend another or self.”

NBC 7 Investigates reached out to the BPD for comment on the report but hasn't heard back. The department disputed the findings of the report to another publication.

“There is a tendency to use the dogs too often, in too many circumstances, just because the option is there,” said animal law expert Ann Schiavone, a professor at Thomas R. Kline School of Law of Duquesne University.

Making matters more complicated, people who face a police dog are not only likely unarmed, but they are also likely experiencing a severe mental episode, according to the ACLU report.

Nearly half of Californians severely injured or killed by police dogs showed signs of a mental health disability or crisis, the report found.

That reality raises serious ethical questions, according to animal law expert Ann Schiavone, who disagrees with SDPD’s classification of dogs as a “de-escalation tool.”

“The use of a dog can make things much worse,” says Schiavone.

The human heart beats faster and adrenaline spikes in the presence of any animal predator, says Schiavone. This coupled with the fact that drugs, alcohol, and mental illness can impair a person’s ability to even recognize police commands, is why Schiavone asks whether police dogs are ever really “reasonable,” in her legal research paper on the legal and moral dilemmas surrounding police dogs.

“The minute someone is attacked by a dog, if they fight back, deadly force is going to be justifiable. So you’ve put that person in a catch-22,” said Schiavone. “We can care about the animals, and care about the animals being killed. But we can also care about those people that are on the other side. And recognize that really the animal and the person have been put in a bad situation.”

A deadly police shooting in Little Italy

A bad situation is essentially how the San Diego County District Attorney summed up what happened inside a Little Italy apartment two years ago.

In the early afternoon of March 3, 2022, a deputy knocked on the door of Yan Li, a 47-year-old Yale-educated scientist, to deliver an eviction notice. A little over an hour later Li was shot dead and an SDPD K-9 handler walked away with a stab wound.

Seconds after Li opened her door, a San Diego County Sheriff’s Department (SDSO) deputy saw a kitchen knife in her hand. He immediately drew his gun, pointed it at Li and started shouting orders for her to drop it, as depicted in body-worn camera video released by SDSO.

The body camera footage shows Li repeatedly ignoring orders to drop her knife. You can hear Li yelling “fake cop” at the deputy multiple times and yelling for someone to “call the police,” before raising her knife, throwing down the paperwork and slamming her door.

Li’s adult son says his mother had been cooking, and says she had a history of mental illness – something the DA’s review acknowledged was likely a factor in what happened.

More deputies and an SDPD K-9 unit were called in to help. The K-9 handler and dog joined a line of deputies who entered Li’s apartment armed with a bean bag shotgun and a pepper ball gun.

Li reacted by raising her knife and walking towards the officers. The officers retreated but not before she stabbed the K-9 handler. You can see him fall to the ground on top of several deputies in the hallway outside Li’s apartment. According to the DA’s report, Li appears to lunge again at the group of officers, but two deputies and the K-9 handler open fire, killing Li.

Before the shooting, one of Li’s neighbors told the deputies they believed Li had a mental illness and offered to help talk her down, according to the DA’s report. That neighbor also said Li was terrified of dogs - so much so that dog owners in the building avoided her, and even knew never to share an elevator with her when with their dog.

Li’s son has filed a federal wrongful death lawsuit against the City of San Diego and San Diego County, claiming officers mishandled the situation when his mother was “clearly in a state of mental crisis…rather than deploying force against the decedent, the officers should have summoned mental health assistance.” That federal case is ongoing.

While the DA’s office acknowledged Li was likely experiencing a mental episode, the office cleared officers from any criminal charges.

“...mental illness may affect an individual’s ability to understand or comply with commands from peace officers,” concluded the DA’s office in its review finding no criminal liability on behalf of the deputies or officers. “In this case, it is reasonable to conclude that Dr. Li was experiencing a mental health crisis, however Dr. Li’s actions constituted an imminent threat to the peace officers, resulting in her tragic death.”

A racial disparity of suspects bitten by K-9s

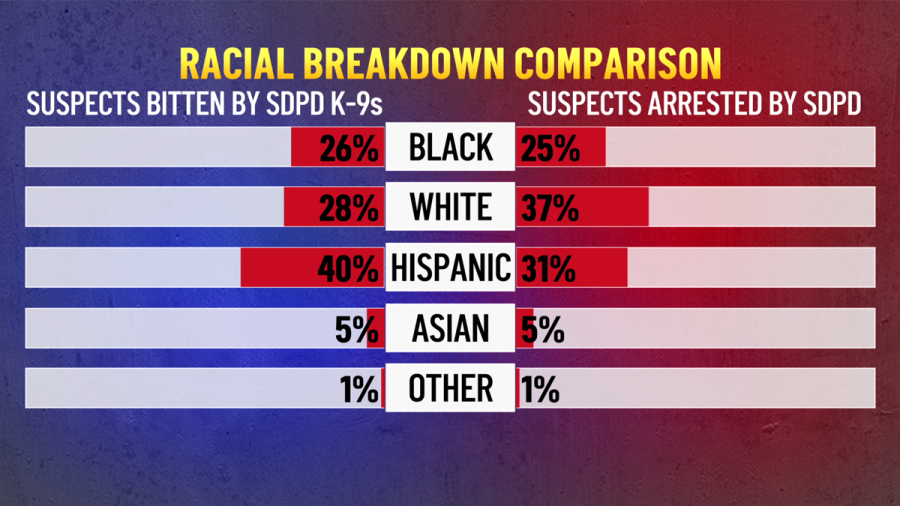

Attacking suspects of non-violent or minor crimes, and/or suspects experiencing mental illness, are not the only uses of K-9s that are facing scrutiny. There’s also the subject of the color of skin on the receiving end of a police dog’s teeth.

A national investigation by the Marshall Project found most bite victims are men, and in some places, disproportionately Black.

An investigation into the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department in 2013 found during the first six months of the year, dogs exclusively bit Black and Hispanic people. Eight years of dog data before that didn’t look much better for the department. Between 2004 and 2012, 89% of total bites were of Black and Hispanic people.

Here in San Diego, SDPD provided NBC 7 Investigates with five years of its K-9 bite data. Between 2018 and 2022, San Diego police dogs bit 161 people. Two-thirds of them, 66%, were Black or Hispanic, despite the fact that they comprise only 36% of the city’s population, according to U.S. Census data.

“I think using demographics to look at crime is not a good scientific method to use,” said Chief Nisleit, when asked about the disproportionate number of Black and Brown people bitten by dogs.

He argues the decision to release a dog, and thus to allow a dog to bite, is not one made by the handler, but rather, “that’s a choice by the suspect.”

“This is a reactive tool,” said Nisleit. “That suspect is given ample opportunities to surrender before a K-9 is sent. So to me, if you don’t want to meet one of our K-9s, don’t commit violent crimes. And then, surrender. If you don’t surrender, there’s a good chance you will be bit by a K-9.”

SDPD did point to other statistics, which show less of a disparity between the types of people that are bitten police K-9s and those that are arrested by their officers.

But Branden Sigua with the ACLU says he believes race does factor into the decision to release a police dog, and he cited a high-profile San Diego incident as the reason why.

Three years ago, body camera footage released from an internal affairs investigation captured an SDPD sergeant saying a police dog “only likes dark meat.”

“That sticks out,” said Sigua. “When you say that K-9 dog bites aren’t racial, it’s hard to make that argument when the people handling these K-9s are explicitly naming that as a factor.”

SDPD suspended the sergeant for eight days, transferred him to another division and required him to attend 40 hours of cultural diversity training.

“You can sit there and highlight bad officers and you’re going to get that perspective that there’s a problem,” said PORAC president Brian Marvel. “But the reality is, I think if you looked at the statistics, the vast majority of officers are being handled appropriately by their agencies.”

Chief Nisleit agrees, saying SDPD has done a “very good job of policing themselves.” A big reason why he supports AB 3041, is because he says it would change very little, if anything at all, about how San Diego’s police dogs operate.

That lack of reform is exactly why the ACLU of Southern California opposes the passage of either bill.

Senior policy advocate Branden Sigua says the solution to California’s unregulated use of police dogs is strict limitations surrounding arrests – not tasking a state police commission to create its own rules.

“These bills fall short of real accountability,” said Sigua.