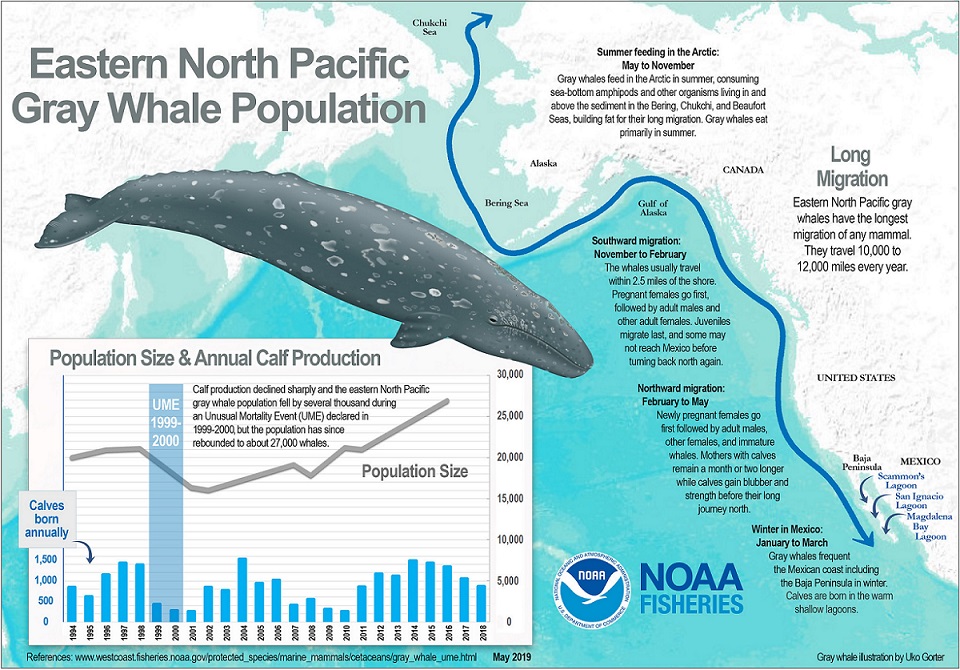

Twice a year, pods or groups of gray whales head south along the San Diego coastline to give birth in the warm lagoons of Mexico's Baja Peninsula. Then, in early spring, they head north to fatten up in the Bering and Chukchi seas. Researchers say this migration is the longest documented journey of any mammal.

But now, many oceanographers have growing concerns about the number of gray whale deaths discovered during their 10,000 mile journey. The reasons behind the deaths are up for debate.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA,) in 2014, 33 gray whales washed ashore along the western North American coastline. But so far in 2019, 86 gray whale carcasses were discovered up and down the coast, some of which were found in Solana Beach, Carlsbad and San Onofre.

Gray Whale Deaths Mapped Since 2015

Since 2015, the number of gray whales dying along the North American coastline has been on the rise, including whales washing ashore in Solana Beach, Carlsbad and San Onofre. Data provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) show the deaths are along the gray whales’ migration route.

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NOAA calls the spike in gray whale deaths as an “unusual mortality event” and while there is no definitive explanation as to what is happening, some scientists say they suspect the melting polar icecap is to blame while other scientists say it's part of a naturally recurring cycle.

In May, many scientists in the San Ignacio Lagoon in Mexico's Baja Peninsula found the gray whales were arriving later than usual this year.

In addition, researchers found gray whale calves weighed less than in previous years.

“In a normal year, only about 10 percent of the whales would be what you’d call in ‘poor condition’” says Aaron Thode, a researcher oceanographer for the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. But this year, Thode said researchers found 25 percent of the mothers and calves appeared to be malnourished.

Researchers found there were fewer gray whales migrating. Thode said normally researchers would see 200 mothers and their calves each year. But so far in 2019, researchers have counted only 20.

Researchers have launched drones over the San Ignacio Lagoon to determine how many whales have migrated south, and to document their size.

Oceanographers are also recording the sounds gray whales make underwater. Eventually, Thode believes the sounds whales use to communicate will help track them, or as he puts it, a way of conducting "an acoustic census."

How Do Gray Whales Communicate?

Researchers say studies into the sounds and acoustic behavior of gray whales are scarce, especially in contrast to other whale species, like humpback whales, whose songs have been the focus of a lot of studies over the years. By determining the reasons behind these gray whale sounds, researchers hope they can learn more about why they are dying off in such high numbers along the west coast.

Audio: Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Whale expert John Calambokidis works from the northern end of the gray whales’ long migration in Olympia, Washington.

He believes for every whale washing ashore, ten more die at sea.

Calambokids says whales are now looking elsewhere for food and ending up in fishing nets, hit by ships or propellers.

With his thirty years of experience, Calambokidis believes this is just the beginning.

“The event isn’t over yet, we’re still in the middle of it.”

There is one way the public can help researchers in their search for answers behind the gray whale deaths and that is calling NOAA if you see a beached or stranded whale. If you see a dead or stranded whale, call the West Coast Marine Mammal Stranding Network at 1-866-767-6114. You can also find more information by clicking here.